“How can the Bible be used with integrity by men and women of faith? How can it be lifted out of prejudices and cultural biases of bygone eras? How can it be a source of life to twentieth and twenty-first century generations? If it continues to be viewed literally, the Bible, in my opinion, is doomed to be cast aside as both dated and irrelevant.” —John Shelby Spong

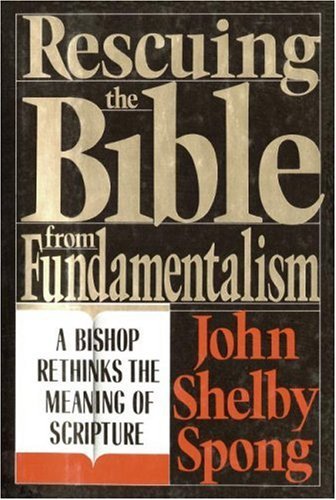

Too often, literal interpretations of the Bible are used to deny human rights on issues ranging from homosexuality to war and retribution. In Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism, Spong speaks out strongly against parochial, chauvinistic interpretations, arguing convincingly that we need to rethink the Bible’s story in light of the realities of modern-day science and contemporary lifestyles.

Spong makes a compelling case for the value of the Bible even when detached from the belief of literal inherency. Much of the book is an argument against inherency, which was the permission I needed to step out of the box of the Bible I’d been taught. I found the context about the writers of the Bible and the processes behind its creation to be illuminating and I enjoyed being given the freedom to engage with the Bible as a historical piece of literature.

But my biggest take away was simply the fact that this book was published in 1991. Spong’s arguments and his information and viewpoints have existed almost my entire life. How am I just hearing about this now? What felt revelatory to me was actually old news—it had just never been presented to me and I didn’t know to go look for it. In my naïveté, I assumed the evangelical church people I grew up with and went to school with just didn’t know—they hadn’t heard the arguments against biblical literalism and inherency and weren’t aware that there could be multiple viewpoints on what it means to be a Bible-reading Christian.

Shortly after returning to the church, I heard a queer pastor redefine the verses used against queerness and explain the nuances of the translation in light of the cultural situations at the time of their writing. I felt so relieved because these views allowed me to put down the weight of trying to reconcile two concepts—love and homophobia—that always felt fundamentally opposed in my soul.

I had been excited to tell a more conservative friend about what I’d learned, thinking her criticisms of my queerness existed just because she didn’t know another way to look at the situation. But she was confident that she had researched the topic and decided the approach I found to be loving simply wasn’t true. “How can you be queer and a Christian?” she asked me. I realized she was choosing this view that was hurting us both and our relationship. Or maybe we were both choosing that hurt in our inability to converse with an open mind.

Why?

Spong ties the rigid belief in Biblical inherency to a sense of religious security that can mitigate people’s fear. But he also acknowledges how futile that is. “Religion almost inevitably tries to take our anxiety away from us by claiming that which religion can never deliver—absolute certainty.” (Pg 170)

I have a hard time coming up with productive questions for more traditionally conservative and evangelical believers. I want to ask: Why are you hurting me and so many others? Why is your spirituality so selfish? Why are you choosing this? But those questions are big questions. Clearly, too big for myself and others to answer.

I think of my cats and the way they are curious. When they find a new object in their world, they approach it slowly and pat, pat, pat it gently, barely moving it at first. And yet somehow, with this method, they get random things all over my apartment in the most surprising locations. The church teaches us to expect big revelations, like a blinding light on a road that causes an immediate, whole-life 180. But maybe in reality, small questions—pat, pat, pat—can move us towards each other and healthy conversations more effectively. What is the smallest question I could use to start a conversation?

My cat Fern reexamining all the things I found underneath my oven drawer. Out of all the options—all the toys I’d bought her—she chose the smallest bit of cardboard to take out of the pile and play with for the rest of the evening.